Printmaking is among the most ancient of human creative expressions. Alongside the

celebrated painted images of Palaeolithic cave art, we find numerous handprints; some created by painting the palm and fingers with liquid ochre and stamping them onto cavern walls, others formed by blowing pigment over the hand to leave a negative impression, encircled by a soft ochre halo.

This instinct to press, stamp, and transfer images has endured through millennia, and

today remains a fundamental part of artistic education. From the simple potato prints of primary school to the more sophisticated techniques of lino and mono printing taught in secondary schools, the tradition continues to evolve.

Early Experiments

Lynn Chadwick’s earliest known prints reflect this same spirit of playful experimentation. His first works were lino-cut Christmas cards (made for friends and family) depicting sculptures he had created that same year or imagined geometric constructions. Often embellished with hand-painted colour or line, each card was unique. Chadwick’s informal approach allowed him to enjoy the process freely, experimenting with coloured inks, textured backgrounds, and personalised variations.

His first formally editioned print came in 1952; a two-colour lithograph depicting seven black-and-white figures on a red ground. Chadwick carefully scraped back areas of red on the lithographic stone to lighten the surrounding tone, drawing the viewer’s eye toward the diamond-shaped spaces between the figures. This early work revealed his fascination with abstract, triangular-based forms.

Methods and Materials

Chadwick’s drawings frequently incorporated printed elements. His enduring interest in triangles, diamonds, and squares - shapes that relate directly to one another - led him to experiment with wooden and glass shapes dipped in ink and pressed to paper. He delighted in the unpredictable textures created within these strict geometric boundaries, adding ruler-printed lines to suggest larger forms or radiating fans reminiscent of the structural rods in his sculpture.

He also employed wax and oil-based resist techniques to create richly textured surfaces, producing marbled and camouflage-like effects that echoed the plastered infills of his sculptures, textures that lent his works their timeless, almost archaeological presence.

Colour was central to Chadwick’s printmaking practice. His hand-coloured variants of, Two Figures - Watchers 1960 demonstrate how he continued to experiment even after completing the lithograph - reversing images, altering colour placements, and exploring tonal and textural variations.

Photography and the Moon

Photography, another of Chadwick’s passions, also inspired his prints. His series The

Moon in Alabama drew upon the early daguerreotype of the moon, whose shadowed crescents and cratered surfaces informed his compositions. The title itself was inspired by Alabama’s role in the development of NASA’s Saturn rockets during the 1950s. Chadwick even purchased a Hasselblad camera, like those used in space photography. The prints’ mottled surfaces, spots, and fingerprints recall both the imperfections of early photograph and the material intimacy of printmaking itself.

His later Moon Series (1965–66) explored a more abstracted vision, incorporating the

rounded corners of early photographs, crescent shapes, and deep shadows to form

eye-like compositions; motifs that echoed contemporaneous sculptures such as Star and Monitor.

Shape and Structure

Chadwick himself noted that as a child, he would arrange triangular and square “Lotts” bricks into lines and shapes on the floor of his bedroom; an early impulse that became a fundamental influence on his sculpture, drawing, and printmaking. This connection is most clearly seen in the Trig series (I–IV), where he composed figures entirely from triangular wooden blocks, using simple mono-printing methods that he later translated into sophisticated lithographs.

Even Beast (1950) began as a triangle drawn with the inked edge of a ruler and embellished with vigorous calligraphic marks; so successful in its simplicity that Chadwick reissued it as an etching in 2003.

Revisiting and Refining

Throughout his career, Chadwick frequently revisited earlier themes, exploring and refining them across media. Drawing and printmaking provided him with an intimate, immediate way to continue his visual thought process, distilling sculptural ideas to their purest forms.

Chadwick’s prints present a remarkable entry point into his world. They encapsulate all of his great themes; Teddy Boy and Girl, Beasts, Conjunctions, Watchers, Pyramids, Electras and more, and being pre-digital, offer a direct window into his creative process. Free from the physical constraints of sculpture, these works retain a striking freshness and clarity, expressing the same vision that established Chadwick as a defining figure of postwar British art.

Text by Rungwe Kingdon

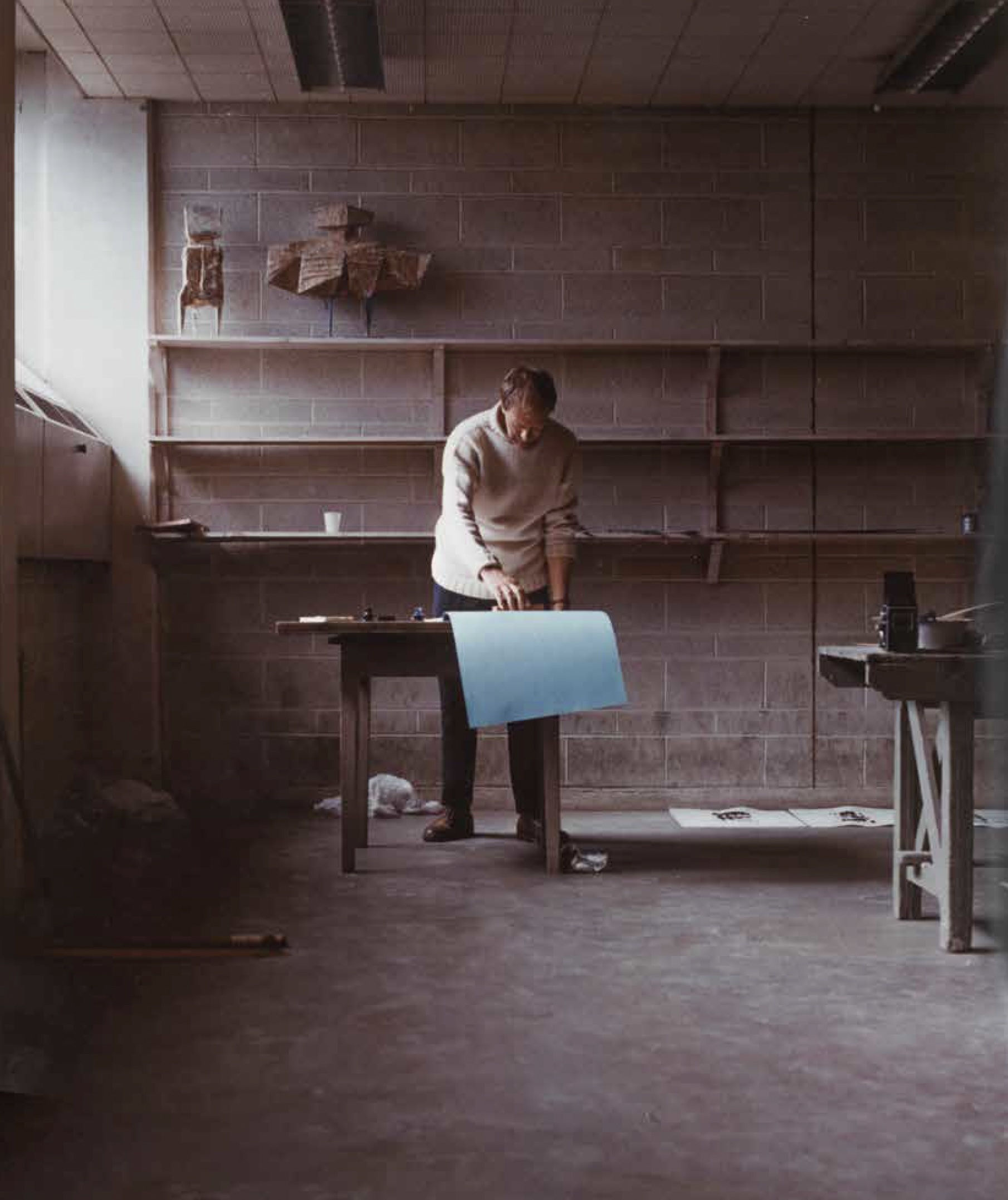

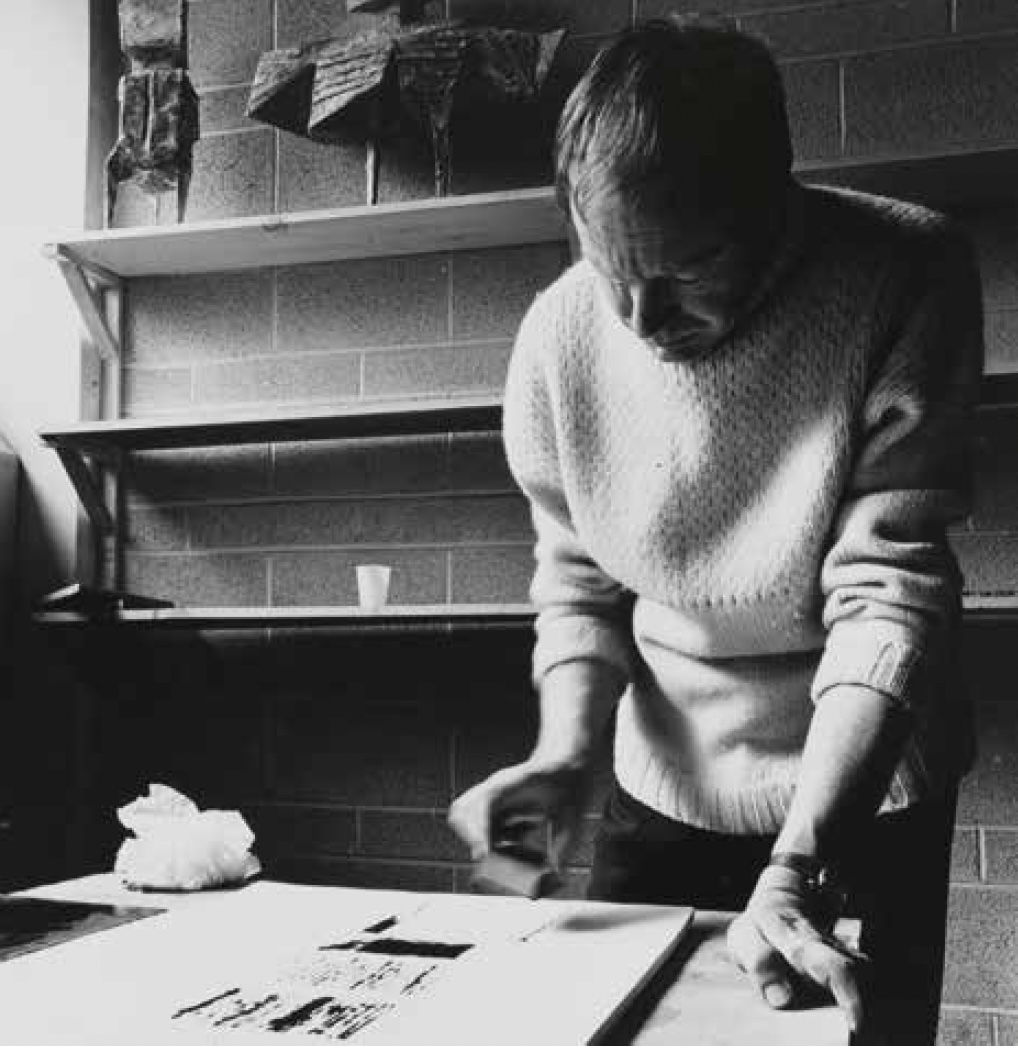

Photos by Peter Croydon